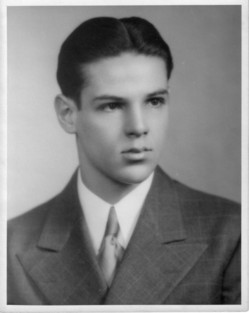

Raymond Joseph Prost

June 20, 1913 – January 5, 2005

In his last years, my father's beautiful soul was burdened with a body that did not move well and a mind that did not remember well, and his release from that prison, although difficult for those left behind, is a blessing.

In his last years, my father's beautiful soul was burdened with a body that did not move well and a mind that did not remember well, and his release from that prison, although difficult for those left behind, is a blessing.

My father was a man to whom words were important. He was a flawless proofreader, a skill picked up in running his business of manufacturing rubber stamps. He was a meticulous wordsmith, and his short stories, poems, letters, and novels are marked by his pursuit of the inevitable phrase. He was a skilled punster, even in his final days in the hospital. He was a top-notch editor, whether teaching writing skills to a grandchild or editing The Serran, the magazine of the organization Serra International, dedicated to fostering vocations to the Catholic priesthood.

My father valued learning. He was an ardent reader and self-taught man. He helped support his parents and family during the Depression, which cost him the chance at higher education, and he was passionate that his daughters would have every educational opportunity.

My father was compassionate. He could never pass a homeless person without offering money. He and my mother took in a foster child, helped his sister raise her children, helped their nephew at a critical juncture in his life, and took care of my mother's dad in his last years.

My father was creative, a skilled carpenter in addition to a writer. He held several patents on inventions such as a double-decker rubber stamp and a camper that mounted in the trunk of a car. His business success, though, was limited by his expectation that his colleagues would be as honorable as he.

My father was a man of spirit. He loved the outdoors, and I never saw him so free as when he sat in a boat in the middle of Osterhout Lake with a fly rod in his hand. For the last 25 years of his life, up until the last week, his response to, "How are you?" was always, "Pretty good for a kid my age."

Above all, my father was a holy man and a believer whose convictions led him to action. His devotion to social justice was deep, and he only came close to losing his faith once, on encountering a segregated Catholic church in Florida which had a set of "Negro" pews in the back. In the 1960s, he quit his job rather than participate in something he felt was unethical, a decision he agonized over because of his responsibility to support his family. One of his greatest food loves was ice cream, which he gave up 40 years ago in thanksgiving for his brother's successful heart surgery. He was a member of the Knights of Columbus and the Holy Name Society and fiercly objected to taking God's name in vain. He said a rosary daily, was a daily communicant for most of his life, and always nudged his descendents toward goodness by word, prayer, and example.

My father was a man of love. He rejoiced in his two daughters, seven grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren (and counting). He honored his wife with a gift on each of the 800 monthly anniversaries of their marriage. The strength and depth of their bond was truly beautiful, and my mother's devotion and care for him in his last years was heroic.

My father was a man of love. He rejoiced in his two daughters, seven grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren (and counting). He honored his wife with a gift on each of the 800 monthly anniversaries of their marriage. The strength and depth of their bond was truly beautiful, and my mother's devotion and care for him in his last years was heroic.

For Tim, Theresa, Thomas, Brendan, and me, it was a great gift to have him and my mother live in Maryland for the past three years, a gift we will always treasure.

Dianne Prost O'Leary

January 2005

My father was a man of love. He rejoiced in his two daughters, seven grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren (and counting). He honored his wife with a gift on each of the 800 monthly anniversaries of their marriage. The strength and depth of their bond was truly beautiful, and my mother's devotion and care for him in his last years was heroic.

My father was a man of love. He rejoiced in his two daughters, seven grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren (and counting). He honored his wife with a gift on each of the 800 monthly anniversaries of their marriage. The strength and depth of their bond was truly beautiful, and my mother's devotion and care for him in his last years was heroic.

In his last years, my father's beautiful soul was burdened with a body that did not move well and a mind that did not remember well, and his release from that prison, although difficult for those left behind, is a blessing.

In his last years, my father's beautiful soul was burdened with a body that did not move well and a mind that did not remember well, and his release from that prison, although difficult for those left behind, is a blessing.